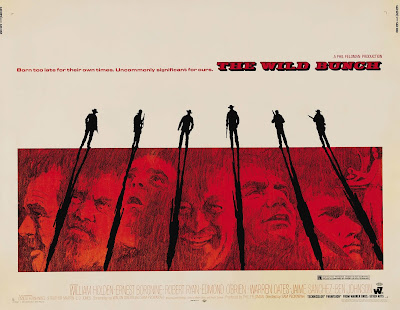

The Wild Violence of 'The Wild Bunch'

Sam

Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch tears at

the screen with blood and violence. The violence in The Wild Bunch is not only historical but also revolutionary. While

the film is one of the most controversial movies of its time, today, its

controversy remains a frequently revisited and debated subject among scholars,

critics, and movie patrons (Gronstad 167). When The Wild Bunch was first release in 1969, critics and general

audiences were incredibly divided (Ferrera). Many critics embraced Peckinpah’s

vision and use of violence and blood. Others admonished Peckinpah for his

brutality and vivid portrays of on-screen violence. Some may feel as though the

violence of The Wild Bunch is

antiquated when compared to the portrayals of on-screen violence seen today.

However, according to Ferrera, the way Peckinpah uses violence changed how filmmakers

portray violence, in particular gun violence, on screen. Unlike previous

western films, Peckinpah showed audiences that death and violence are bloody

and miserable. Even today, the graphic violence in The Wild Bunch is a

subject of controversy and debate. Despite the controversy of the past and

present that obsesses on Peckinpah’s use of violence, blood and guns, The Wild Bunch remains of the most

celebrated and influential American Westerns of all time.

Sam

Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch tears at

the screen with blood and violence. The violence in The Wild Bunch is not only historical but also revolutionary. While

the film is one of the most controversial movies of its time, today, its

controversy remains a frequently revisited and debated subject among scholars,

critics, and movie patrons (Gronstad 167). When The Wild Bunch was first release in 1969, critics and general

audiences were incredibly divided (Ferrera). Many critics embraced Peckinpah’s

vision and use of violence and blood. Others admonished Peckinpah for his

brutality and vivid portrays of on-screen violence. Some may feel as though the

violence of The Wild Bunch is

antiquated when compared to the portrayals of on-screen violence seen today.

However, according to Ferrera, the way Peckinpah uses violence changed how filmmakers

portray violence, in particular gun violence, on screen. Unlike previous

western films, Peckinpah showed audiences that death and violence are bloody

and miserable. Even today, the graphic violence in The Wild Bunch is a

subject of controversy and debate. Despite the controversy of the past and

present that obsesses on Peckinpah’s use of violence, blood and guns, The Wild Bunch remains of the most

celebrated and influential American Westerns of all time.

Perhaps

the most intriguing aspect of The Wild

Bunch’s reception is the debate among popular critics around the time of

the film’s release. Film audiences had not seen explicit portrayals of violence

before Peckinpah’s masterpiece (Ferrera). Bullet holes rip through clothing and

human bodies, and blood gushes as the bullets rip through a character’s body.

Peckinpah showed the killing of innocent bystanders. The perpetrators of

violence use other humans as shields from cascades of bullets. Children giggle

as hordes of ants devour a scorpion alive, and later, the children set fire to both

the scorpions and ants. The aftermath of gun battle in The Wild Bunch is gruesome and scary. The brightest color in the

film is blood. For its time, the violence of The Wild Bunch was unmatched, and many critics and audience members

were unsettled and outraged (Canby). Vincent Canby of The New York Times suggests that other critics of the time seemed

to have felt as though the film would cause viewers to want to leave the theater

and automatically start murdering people. Canby affirms that an impulse to

inflict violence on people was not present after watching The Wild Bunch, and the film, “Is very beautiful and the first

truly interesting, American-made Western in years.”

Although

many critics felt as though the film was too violent and not suitable for

humanity, Charles Champlin and Roger Ebert celebrated the film. Champlin often

squinted during the film in a futile attempt to escape the violence. He refers

to The Wild Bunch as, “Not so much a

movie as a blood bath,” but affirms that the film is, “Brilliantly made and

thought provoking.” Champlin notes the original test audiences of The Wild Bunch recoiled in horror and

stormed out of the theaters in droves. Apparently, members of test screenings

picketed the theaters the next day, and Warner Brothers made Peckinpah cut 35

minutes of violence before officially releasing the film (Champlin). However,

Champlin defended the film’s portrayal of violence, and notes that death in The Wild Bunch is depraved and gut

wrenching, just as it is in real life. Roger Ebert also celebrated and defended

the film’s use of violence with veracity and eloquence. Ebert affirms that the

larger cultural issue at hand is that we depict cowboys, Indians, and the Old

West as a fun game for children to play.

While Peckinpah did not make a cowboys

and Indians film, The Wild Bunch attacks

and destroys the notion of the traditional Western. Ebert notes that Peckinpah

utilized excessive violence, but this violence merely comes as a reaction and a

response to violence enacted throughout the world on a daily basis. This

response to violence continues to reverberate through modern-day culture and

violence. After seeing The Wild Bunch a

second time, Ebert described some of

Peckinpah’s use of violence as, “Blood flowing in an unending stream” and

“Geysers of blood everywhere.” While Peckinpah’s use of violence is graphic and

unlike any other film of its time, interestingly, Ebert’s statements were

hyperbole. Nonetheless, Ebert argues that regardless of how graphic and

realistic Peckinpah’s on-screen violence may have been, the film exists in a

one-dimensional realm, realism is not synonymous with reality, and it is

“Impossible to forget this is a movie.”

While Peckinpah did not make a cowboys

and Indians film, The Wild Bunch attacks

and destroys the notion of the traditional Western. Ebert notes that Peckinpah

utilized excessive violence, but this violence merely comes as a reaction and a

response to violence enacted throughout the world on a daily basis. This

response to violence continues to reverberate through modern-day culture and

violence. After seeing The Wild Bunch a

second time, Ebert described some of

Peckinpah’s use of violence as, “Blood flowing in an unending stream” and

“Geysers of blood everywhere.” While Peckinpah’s use of violence is graphic and

unlike any other film of its time, interestingly, Ebert’s statements were

hyperbole. Nonetheless, Ebert argues that regardless of how graphic and

realistic Peckinpah’s on-screen violence may have been, the film exists in a

one-dimensional realm, realism is not synonymous with reality, and it is

“Impossible to forget this is a movie.”

While Peckinpah did not make a cowboys

and Indians film, The Wild Bunch attacks

and destroys the notion of the traditional Western. Ebert notes that Peckinpah

utilized excessive violence, but this violence merely comes as a reaction and a

response to violence enacted throughout the world on a daily basis. This

response to violence continues to reverberate through modern-day culture and

violence. After seeing The Wild Bunch a

second time, Ebert described some of

Peckinpah’s use of violence as, “Blood flowing in an unending stream” and

“Geysers of blood everywhere.” While Peckinpah’s use of violence is graphic and

unlike any other film of its time, interestingly, Ebert’s statements were

hyperbole. Nonetheless, Ebert argues that regardless of how graphic and

realistic Peckinpah’s on-screen violence may have been, the film exists in a

one-dimensional realm, realism is not synonymous with reality, and it is

“Impossible to forget this is a movie.”

While Peckinpah did not make a cowboys

and Indians film, The Wild Bunch attacks

and destroys the notion of the traditional Western. Ebert notes that Peckinpah

utilized excessive violence, but this violence merely comes as a reaction and a

response to violence enacted throughout the world on a daily basis. This

response to violence continues to reverberate through modern-day culture and

violence. After seeing The Wild Bunch a

second time, Ebert described some of

Peckinpah’s use of violence as, “Blood flowing in an unending stream” and

“Geysers of blood everywhere.” While Peckinpah’s use of violence is graphic and

unlike any other film of its time, interestingly, Ebert’s statements were

hyperbole. Nonetheless, Ebert argues that regardless of how graphic and

realistic Peckinpah’s on-screen violence may have been, the film exists in a

one-dimensional realm, realism is not synonymous with reality, and it is

“Impossible to forget this is a movie.”

In

addition to the variety of responses and debate among film critics and audience

members at the time of The Wild Bunch’s release,

controversy and commentary continues in modern times. Books, scholarly

articles, and blogs continue to chronical and add to the discussion of

Peckinpah’s portrayal of on-screen violence in The Wild Bunch. In Cowboy Metaphysics, Peter A. French does

not share the same spirit of support for Peckinpah’s portrayals of violence as Roger

Ebert. French categorizes Peckinpah’s use of violence as simply an, “Extreme

consciousness of death” (84). According to French, the main characters are

courageous and heroic, but they are slightly demonic and lack true altruism in

their supposedly heroic actions (126). The concept of a person committing to

their word as the single attribute necessary to achieve the highest level of

moral integrity in The Wild Bunch is

particularly unsettling to French. French argues that this brand of integrity

utilized in The Wild Bunch causes one

to overlook the appalling traits and violence behavior of the film’s characters

(128). In other words, if a character is seen as possessing integrity, their

awful behavior is justified, and to a certain degree integrity becomes a device

that glorifies violent acts regardless of whether the violence is justifiable

or not.

Meanwhile,

critical researcher Asbjorn Gronstad highlights and supports many critically

justifiable functions of Peckinpah’s use of violence. Gronstad compares

Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch to Thoreau’s Walden, not in plot but in

meaning and allegory (169). According to Gronstad, morality is not the

overarching theme of the film and its violence. Instead, the film is an

allegory for the battle between nature and technological progress (Gronstad 170).

Observing and drawing conclusions solely from the lens of morality not only

negates Peckinpah’s sense of morality, but also ignores a deeper and important

thematic dynamic at play in The Wild Bunch. Gronstad frames Peckinpah’s

portrayals of violence as both an admonishment of violence and violence toward,

“Socio-cultural homogenization” (169). Additionally, Gronstad claims that by

re-representing the past, specifically the Old West, in a more appropriate and

accurate light, viewers are able to draw a correlation to the present and

possible futures of humanity (171). In order to understand the present, and

violence situated in the present, we must work to stop glorifying the past.

Violence is not a virtue to Peckinpah. Instead, Peckinpah depicts violence as a

product of a bleak world in which humanity is always at odds with machine, and

in this world, there is no hope for the past, present, or future (Gronstad

184).

Meanwhile,

critical researcher Asbjorn Gronstad highlights and supports many critically

justifiable functions of Peckinpah’s use of violence. Gronstad compares

Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch to Thoreau’s Walden, not in plot but in

meaning and allegory (169). According to Gronstad, morality is not the

overarching theme of the film and its violence. Instead, the film is an

allegory for the battle between nature and technological progress (Gronstad 170).

Observing and drawing conclusions solely from the lens of morality not only

negates Peckinpah’s sense of morality, but also ignores a deeper and important

thematic dynamic at play in The Wild Bunch. Gronstad frames Peckinpah’s

portrayals of violence as both an admonishment of violence and violence toward,

“Socio-cultural homogenization” (169). Additionally, Gronstad claims that by

re-representing the past, specifically the Old West, in a more appropriate and

accurate light, viewers are able to draw a correlation to the present and

possible futures of humanity (171). In order to understand the present, and

violence situated in the present, we must work to stop glorifying the past.

Violence is not a virtue to Peckinpah. Instead, Peckinpah depicts violence as a

product of a bleak world in which humanity is always at odds with machine, and

in this world, there is no hope for the past, present, or future (Gronstad

184).  While

controversy and debate about Peckinpah’s use of violence continues over 40

years after the film’s release, The Wild Bunch remains a, “Seminal work

of violence and artistry that forever changed the landscape of motion pictures”

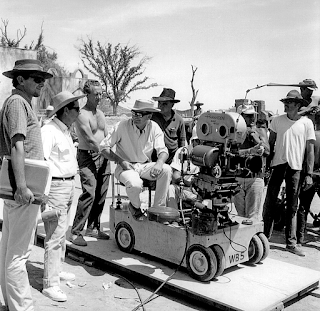

(Ferrara). According to Ferrara, Peckinpah was the first to use violence as a

slowed-down, graphically choreographed visual motif. The sound of flies buzzing

over dead bodies, squibs aggressively flinging blood across the screen,

different angles of the same action, and the double and triple printing of film

were all innovative techniques Peckinpah utilized to depict on-screen violence

(Ferrara). While these techniques are a victory of filmmaking that many

filmmakers utilize today, they are also the source of much of The Wild

Bunch’s controversy. Prior to The Wild Bunch’s release, the

Production Code had not yet been eradicated (Ferrara). According to Ferrara,

the Production Code was eventually eradicated and replaced by the MPAA, yet the

MPAA strongly objected to the violence and required Peckinpah to remove a scene

that graphically displays the cutting of a character’s throat. Upon test screening the film, after making the

necessary cuts, audience members’ reactions were often extremely negative, and

Ferrara quotes one early audience member saying, “Don’t release this film. The

whole thing is sick.” Despite the controversy and the MPAA’s objections to the

depictions of violence in The Wild Bunch, the film received several

prestigious awards. In 1999, The Wild Bunch was added to the National

Film Registry (Ferrara).

While

controversy and debate about Peckinpah’s use of violence continues over 40

years after the film’s release, The Wild Bunch remains a, “Seminal work

of violence and artistry that forever changed the landscape of motion pictures”

(Ferrara). According to Ferrara, Peckinpah was the first to use violence as a

slowed-down, graphically choreographed visual motif. The sound of flies buzzing

over dead bodies, squibs aggressively flinging blood across the screen,

different angles of the same action, and the double and triple printing of film

were all innovative techniques Peckinpah utilized to depict on-screen violence

(Ferrara). While these techniques are a victory of filmmaking that many

filmmakers utilize today, they are also the source of much of The Wild

Bunch’s controversy. Prior to The Wild Bunch’s release, the

Production Code had not yet been eradicated (Ferrara). According to Ferrara,

the Production Code was eventually eradicated and replaced by the MPAA, yet the

MPAA strongly objected to the violence and required Peckinpah to remove a scene

that graphically displays the cutting of a character’s throat. Upon test screening the film, after making the

necessary cuts, audience members’ reactions were often extremely negative, and

Ferrara quotes one early audience member saying, “Don’t release this film. The

whole thing is sick.” Despite the controversy and the MPAA’s objections to the

depictions of violence in The Wild Bunch, the film received several

prestigious awards. In 1999, The Wild Bunch was added to the National

Film Registry (Ferrara).  Peckinpah’s

own reaction to The Wild Bunch’s release is perhaps one of the most

compelling commentaries on the film’s use of violence. Even though there were

several audience members that recoiled in horror and condemned the violence in

the film, Peckinpah was more appalled by stories of audience members that

cheered and attained enjoyment from the film’s violence (Ferrara). Nonetheless,

Peckinpah ultimately defended his depictions of violence when condemned by

critics, and Peckinpah condemned the idea that he was using on-screen violence

as something that is fun and enjoyable (Ferrara). While Peckinpah romanticized

the beautiful Mexican landscape in which the film is set, the depictions of

violence are brutal, dirty, and devastating. Peckinpah was nicknamed “Bloody

Sam” and the final shoot out of The Wild Bunch the “Blood ballet,” yet Peckinpah

used violence in the film to speak out against the Vietnam War and violence in

general (Ferrara). As Peckinpah himself said, “I wasn't trying to make an epic.

I was trying to tell a simple story about bad men in changing times. I was

trying to make a few comments on violence, and the people who live by violence.”

Peckinpah’s

own reaction to The Wild Bunch’s release is perhaps one of the most

compelling commentaries on the film’s use of violence. Even though there were

several audience members that recoiled in horror and condemned the violence in

the film, Peckinpah was more appalled by stories of audience members that

cheered and attained enjoyment from the film’s violence (Ferrara). Nonetheless,

Peckinpah ultimately defended his depictions of violence when condemned by

critics, and Peckinpah condemned the idea that he was using on-screen violence

as something that is fun and enjoyable (Ferrara). While Peckinpah romanticized

the beautiful Mexican landscape in which the film is set, the depictions of

violence are brutal, dirty, and devastating. Peckinpah was nicknamed “Bloody

Sam” and the final shoot out of The Wild Bunch the “Blood ballet,” yet Peckinpah

used violence in the film to speak out against the Vietnam War and violence in

general (Ferrara). As Peckinpah himself said, “I wasn't trying to make an epic.

I was trying to tell a simple story about bad men in changing times. I was

trying to make a few comments on violence, and the people who live by violence.”

Although

Peckinpah expressed disappointed that audience members were thrilled and

enjoyed the violence, even Roger Ebert admits enjoying Peckinpah’s use of

violence. While audiences were divided on whether certain elements of The

Wild Bunch are enjoyable or detestable, the film depicts violence, death,

and the gun as gruesome and unenjoyable elements of the world. This depiction

was Peckinpah’s goal, and the film does not glorify violence but rather

condemns violence in the world. If nothing else, Peckinpah managed to produce a

violent film that is still a subject of controversy today. Many critiques of The

Wild Bunch, such as French’s Cowboy Metaphysics, paint a grim

picture of how Peckinpah depicted violence in The Wild Bunch. However,

many popular critics and scholars defend Peckinpah’s use and aesthetic of

violence. Ultimately, it seems as though the individuals commenting on the

violence in The Wild Bunch are more obsessed with violence than the film

itself or Peckinpah, because despite the insurmountable amount of commentary on

the violence in The Wild Bunch, I could not find a source that mentions the

film ending in laughter and song.

Although

Peckinpah expressed disappointed that audience members were thrilled and

enjoyed the violence, even Roger Ebert admits enjoying Peckinpah’s use of

violence. While audiences were divided on whether certain elements of The

Wild Bunch are enjoyable or detestable, the film depicts violence, death,

and the gun as gruesome and unenjoyable elements of the world. This depiction

was Peckinpah’s goal, and the film does not glorify violence but rather

condemns violence in the world. If nothing else, Peckinpah managed to produce a

violent film that is still a subject of controversy today. Many critiques of The

Wild Bunch, such as French’s Cowboy Metaphysics, paint a grim

picture of how Peckinpah depicted violence in The Wild Bunch. However,

many popular critics and scholars defend Peckinpah’s use and aesthetic of

violence. Ultimately, it seems as though the individuals commenting on the

violence in The Wild Bunch are more obsessed with violence than the film

itself or Peckinpah, because despite the insurmountable amount of commentary on

the violence in The Wild Bunch, I could not find a source that mentions the

film ending in laughter and song.

Works

Cited

Canby, Vincent. “Violence and

Beauty Mesh in Wild Bunch” 26 June

1969. New York Times... Web. Mar.

2015.

Champlin, Charles. “Violence Runs

Rampant in The Wild Bunch.” Los Angeles Times 15 June,

1969... Web. 1 Mar. 2015.

Ebert, Roger. “The Wild Bunch.” Chicago Sun-Times 3 Aug. 1969. Rogerebert.com, n.d.

Web. 1 Mar 2015.

Ferrara, Greg. The Wild Bunch: Articles. Turner

Classic Movies, Turner Sports and

Entertainment

Digital Network, n.d. Web. 1 Mar 2015.

French, Peter A. Cowboy Metaphysics. Lanham, MD: Rowman

& Littlefield, 1997. Print.

Gronstad, Asbjorn. “Peckinpah’s Walden: The Violent Indictment of

‘Civilization’ in The Wild

Bunch.” Critical Studies 15.1 (2001): 167-186. ASU Library One Search. Web. 1 Mar. 2015.

Peckinpah, Sam, dir. The Wild Bunch. Perf. William Holden,

Ernest Borgnine, and Robert Ryan.

Warner

Brothers/Seven Arts, 1969. Film.