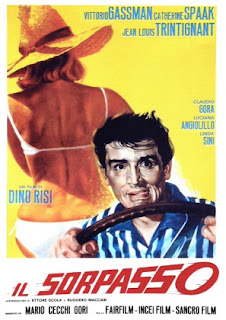

The Easy Life/Il sorpasso (1962)

A

Passing Warning

Il Sorpasso (The Easy Life) is a

ferociously entertaining film that is both masterful and thought provoking. Directed

by Dino Risi, Il Sorpasso stars

Vittorio Gassman as Bruno and Jean-Louis Trintignant as Roberto. Nick Vivarelli

of Variety referred to Risi as, “An

undisputed master of Italy’s postwar commedia all’italiana.” Il Sorpasso demonstrates this sentiment

beautifully. On the surface, Il Sorpasso

is a comedy about a road trip shared by two entirely different strangers. Meanwhile,

the film is also deeply tragic, and it provides a reflection of cultures past

and present. Bruno is the driving force of the film from the beginning to the

end. He is wild and unrestrained. Responsibilities are the furthest issues from

Bruno’s mind. Instead, Bruno lives in every moment with excitement and wanton

disregard for consequences. He charges through life and the Italian landscape

in a peppy little convertible with reckless abandon. However, Bruno’s actions

and carelessness eventually result in the tragic death of Roberto.

Il Sorpasso (The Easy Life) is a

ferociously entertaining film that is both masterful and thought provoking. Directed

by Dino Risi, Il Sorpasso stars

Vittorio Gassman as Bruno and Jean-Louis Trintignant as Roberto. Nick Vivarelli

of Variety referred to Risi as, “An

undisputed master of Italy’s postwar commedia all’italiana.” Il Sorpasso demonstrates this sentiment

beautifully. On the surface, Il Sorpasso

is a comedy about a road trip shared by two entirely different strangers. Meanwhile,

the film is also deeply tragic, and it provides a reflection of cultures past

and present. Bruno is the driving force of the film from the beginning to the

end. He is wild and unrestrained. Responsibilities are the furthest issues from

Bruno’s mind. Instead, Bruno lives in every moment with excitement and wanton

disregard for consequences. He charges through life and the Italian landscape

in a peppy little convertible with reckless abandon. However, Bruno’s actions

and carelessness eventually result in the tragic death of Roberto.

While Bruno

represents a man attempting to transcend his age and a special brand of overcharged

masculinity, Roberto is different. Roberto is quiet and reserved. He is

ordinary and represents the traditional values of Italian men and families

(Candela). From the onset of the film, Bruno makes Roberto nervous, and he is

uncertain of Bruno’s intentions. Although Roberto is uncomfortable in the

beginning, he eventually begins to relax and gives into Bruno’s influence. The

juxtaposition between Bruno’s fun-loving personality and Roberto’s sheltered

nature provides an organic humor. The film is a highly entertaining comedy, yet

it is also a cautionary tale about economic prosperity and a man that lives

without prudence (Powers). While Il

Sorpasso is a depiction of Italy in the 1960s, the film’s humor and themes

transcend geographical borders and time.

One of the most

essential ingredients of Il Sorpasso

is Vittorio Gassman’s performance. Gassman is brilliant as Bruno. Bruno not

only convinces Roberto to ride in his car, but also yanks the audience into the

passenger seat. Although we are also uncertain of Bruno’s motives and question

his level of self-control, we cannot help but join him on his journey. While

Bruno provides a representation of problematic masculinity manifested onscreen

as a lunatic in a convertible, he is also fun, exciting, and infectiously

charming. We see through Roberto that Bruno is not only a potentially dangerous

man, but also a lovable boy trapped in a man’s body. When necessary, Gassman

seamlessly flows in and out of moments of hysterical comedy and the layers of

turmoil that reside within Bruno. Bruno is over the top and out of control, but

Gassman’s performance in Il Sorpasso

is nuanced and refined.

One of the most

essential ingredients of Il Sorpasso

is Vittorio Gassman’s performance. Gassman is brilliant as Bruno. Bruno not

only convinces Roberto to ride in his car, but also yanks the audience into the

passenger seat. Although we are also uncertain of Bruno’s motives and question

his level of self-control, we cannot help but join him on his journey. While

Bruno provides a representation of problematic masculinity manifested onscreen

as a lunatic in a convertible, he is also fun, exciting, and infectiously

charming. We see through Roberto that Bruno is not only a potentially dangerous

man, but also a lovable boy trapped in a man’s body. When necessary, Gassman

seamlessly flows in and out of moments of hysterical comedy and the layers of

turmoil that reside within Bruno. Bruno is over the top and out of control, but

Gassman’s performance in Il Sorpasso

is nuanced and refined.

The nuances and

refinement found in Gassman’s performance harmoniously echo Dino Risi’s

directing. Risi’s emphasis on detail is striking. Every frame of the film seems

to come alive with subtly and superior composition. Bruno is wild and

energetic, but Roberto is calm and restrained. Risi’s directing style

demonstrates the same type of relationship. Risi balances each of these forces

with control and elegance. Risi can be loud and over the top, yet much like

Roberto, he remains in the background in quiet contemplation when necessary.

The framing of the characters and the landscape of the film are accomplished

with precision. Everyone and everything in the camera’s lens is carefully

constructed, and Risi gives purpose to both the central characters and the

extras. Risi’s extras are almost just as important as the central characters of

the film. By drawing our attention to these branches of reality and alternate

modes of existence, Risi adds a depth that assists in bringing the film alive. These

details not only provide the audience a greater sense of the world that

surrounds Bruno and Roberto, but also a unique perspective of Italy during the

postwar economic boom (Lopate).

From the moment

the film opens, Risi captivates the audience with visually striking landscapes.

A lively jazz soundtrack blares through the psyche. Although the streets of

Italy are mostly empty, Bruno and his convertible fill the landscape with

energy and excitement. The tone of the film is carefully set. When Bruno stops

the car outside Roberto’s home in the beginning of the film, the audience becomes

a passenger before Bruno and Roberto meet. Bruno and Roberto are strangers, but

Bruno’s overbearing and outgoing personality instantly engulf Roberto’s

existence. Upon meeting one another, Bruno asks Roberto to call a woman that is

waiting for Bruno. Instead of calling the woman for Bruno, Roberto invites

Bruno to use his phone. Roberto is timid and reclusive. He wants to be alone to

study, but Bruno quickly convinces Roberto to take a drive in the convertible.

Bruno’s driving is erratic and dangerous. He roars through the Italian

landscape, furiously honking his horn, and teasing everyone that he passes.

While Bruno mocks everyone that he passes, Risi mocks Bruno’s machismo and

masculinity throughout the entire film. Despite the comedy that Risi uses to

poke fun at his characters and Italy, a deep affection for the characters and country

is apparent in Risi’s work.

As Bruno and

Roberto drive from town to town, Bruno is never in short supply of sarcasm and

practical jokes. He plays jokes on Roberto, the people he meets, and other cars

on the road. At first, Bruno’s behavior and bravado make Roberto uneasy, and he

questions whether he should continue to engage in the car ride with Bruno.

However, eventually Roberto warms up to Bruno, and it is apparent that Roberto

admires Bruno. Bruno’s overbearing personality lures Roberto into Bruno’s way

of life. Bruno charges through the world with the carefree nature of a child.

While Bruno is uninhibited around women, Roberto is shy and nervous around them.

However, as he begins to loosen up and enjoy the ride in Bruno’s convertible,

Roberto starts to enjoy the simple pleasures of life with Bruno.

However, eventually Roberto warms up to Bruno, and it is apparent that Roberto

admires Bruno. Bruno’s overbearing personality lures Roberto into Bruno’s way

of life. Bruno charges through the world with the carefree nature of a child.

While Bruno is uninhibited around women, Roberto is shy and nervous around them.

However, as he begins to loosen up and enjoy the ride in Bruno’s convertible,

Roberto starts to enjoy the simple pleasures of life with Bruno.

However, eventually Roberto warms up to Bruno, and it is apparent that Roberto

admires Bruno. Bruno’s overbearing personality lures Roberto into Bruno’s way

of life. Bruno charges through the world with the carefree nature of a child.

While Bruno is uninhibited around women, Roberto is shy and nervous around them.

However, as he begins to loosen up and enjoy the ride in Bruno’s convertible,

Roberto starts to enjoy the simple pleasures of life with Bruno.

However, eventually Roberto warms up to Bruno, and it is apparent that Roberto

admires Bruno. Bruno’s overbearing personality lures Roberto into Bruno’s way

of life. Bruno charges through the world with the carefree nature of a child.

While Bruno is uninhibited around women, Roberto is shy and nervous around them.

However, as he begins to loosen up and enjoy the ride in Bruno’s convertible,

Roberto starts to enjoy the simple pleasures of life with Bruno.

Until the end of

the film, Bruno seems without consequence, and he often slips away from danger

and authority unscathed. Bruno seems unstoppable until a car crash on the side

of the road prompts him to pull over. A dead body lies on the side of the road.

Instead of taking the serious nature of the car crash to heart, Bruno remains

sarcastic, opportunist, and flippant. He attempts to capitalize on the

situation by soliciting a crying truck driver for the merchandise damaged in

the crash. However, a police officer quickly interrupts Bruno by honking the

convertible’s ridiculous car horn. The police officer writes Bruno a ticket for

his reckless driving. Despite the officer’s citation and the foreshadowing

implored by a dead body on the side of the road, Bruno remains obnoxious. Bruno

begins mocking the police officer, but he is quickly back on the road racing

through life more carefree than ever.

Throughout the

film, it often seems as though there is no stopping or slowing down Bruno. His

vibrant energy never falters. Until we

learn the Bruno has a wife and daughter, it seems that Bruno has led an

entirely laid-back and untroubled life. However, as Bruno’s estranged wife

Gianna reveals to Roberto, Bruno has struggled to find his place in the world.

Underneath the seemingly happy-go-lucky and brash exterior of Bruno, resides a

lonely boy that never matured. In fact, Bruno’s teenage daughter Lilly is more

mature and self-controlled than Bruno. Once Lilly and Gianna are introduced, it

is clear that the lifestyle Bruno leads and the unfaltering masculinity that he

clings to have already resulted in negative consequences. It is obvious that

Bruno has been absent for the majority of Lilly’s life. Meanwhile, it is

apparent that Lilly loves and cares for Bruno, but Lilly generally uses Bruno’s

first name when talking to him. She sees Bruno as more of a friend than she

does a father figure.

In the middle of

the night, Bruno and Roberto arrive at Gianna’s house drunk. Shortly after

their arrival, Lilly’s boyfriend Bibi escorts her home. Bibi is significantly

older than Bruno, and Bibi’s age upsets Bruno. However, Roberto offsets Bruno’s

frustration by drunkenly laughing at the situation. The presence of Bibi, and

Lilly’s plans to move to America with Bibi, mark the point in which Bruno

finally begins to question and evaluate the choices that he has made in life. Lilly’s

relationship with Bibi is an obvious representation of a young girl seeking out

the male role model and fatherly structure that Bruno neglected to provide

Lilly in her formative years. Meanwhile, Lilly’s relationship with Bibi is not

a manifestation of malice or passive aggressive vengeance. Bruno regrets not

being a better father to Lilly and a more responsible person in general.

However, when Bruno confides in Lilly, Lilly tells Bruno that he should never

change. She cannot help but love Bruno and his vivacious attitude toward life.

In the middle of

the night, Bruno and Roberto arrive at Gianna’s house drunk. Shortly after

their arrival, Lilly’s boyfriend Bibi escorts her home. Bibi is significantly

older than Bruno, and Bibi’s age upsets Bruno. However, Roberto offsets Bruno’s

frustration by drunkenly laughing at the situation. The presence of Bibi, and

Lilly’s plans to move to America with Bibi, mark the point in which Bruno

finally begins to question and evaluate the choices that he has made in life. Lilly’s

relationship with Bibi is an obvious representation of a young girl seeking out

the male role model and fatherly structure that Bruno neglected to provide

Lilly in her formative years. Meanwhile, Lilly’s relationship with Bibi is not

a manifestation of malice or passive aggressive vengeance. Bruno regrets not

being a better father to Lilly and a more responsible person in general.

However, when Bruno confides in Lilly, Lilly tells Bruno that he should never

change. She cannot help but love Bruno and his vivacious attitude toward life.

Nonetheless, Bruno’s

unfaltering reckless behavior ultimately causes Roberto’s death. After a brief respite

at the beach, Bruno and Roberto decide to end their road trip. Bruno is just as

careless and fearless as even while driving home. Despite Roberto’s fear and

uncertainty of Bruno’s reckless driving in the beginning of the film, in the

end, he relishes in the excitement of speeding through the Italian landscape. Now,

both Bruno and Roberto are screaming and wailing down the highway like two

teenagers on a joyride. As Bruno attempts another il sorpasso (the suiting

title and Italian term for aggressively passing another vehicle,) he drives the

convertible into oncoming traffic, and a semi-truck drives straight at the

convertible (Lopate). Bruno swerves the car away from a semi-truck. He loses

control of the car. The car smashes into a cement barricade. The impact of the

crash throws Bruno from the car as it tumbles down a cliff. Roberto remains in

the passenger seat as the car falls, and he plunges to his death.

While Il Sorpasso is a highly entertaining

comedy, it is also a deeply tragic film. It is not only a social critique about

Italian males and the economic boom of postwar Italy, but also a warning

(Powers). Despite the excitement inherent in Bruno’s vibrant and arrogant

personality, his carefree lifestyle results in detrimental consequences. Bruno

embraced a frivolous and superficial lifestyle, and he can only blame himself

for missing his child’s life and the death of Roberto. Additionally, the film

serves as a reflection of a culture and a society that Risi saw as speeding

recklessly out of control trying to breeze by anyone or anything it passes

(Lopate). The film warns that life can be thrilling and fun. However, when we

stop paying attention to that which we care about and lose sight of ourselves,

tragedy waits down the road.

While Il Sorpasso is a highly entertaining

comedy, it is also a deeply tragic film. It is not only a social critique about

Italian males and the economic boom of postwar Italy, but also a warning

(Powers). Despite the excitement inherent in Bruno’s vibrant and arrogant

personality, his carefree lifestyle results in detrimental consequences. Bruno

embraced a frivolous and superficial lifestyle, and he can only blame himself

for missing his child’s life and the death of Roberto. Additionally, the film

serves as a reflection of a culture and a society that Risi saw as speeding

recklessly out of control trying to breeze by anyone or anything it passes

(Lopate). The film warns that life can be thrilling and fun. However, when we

stop paying attention to that which we care about and lose sight of ourselves,

tragedy waits down the road.

Works Cited

Candela, G. “Il Sorpasso.” Arizona State University. G. Homer

Durham Language

and Literature

building, Tempe, AZ. Oct. 2015. Lecture.

Il Sorpasso. Dir. Dino Risi. Perf. Vittorio Gassman

and Jean-Louis Trintignant. Criterion, 2014.

DVD.

Lopate, Phillip. “Il sorpasso: The Joys of

Disillusionment.” Criterion. The

Criterion Collection,

n.d. Web. 20 Nov.

2015

Powers, John. “Two Italys Take a

Road Trip in Il sorpasso.” NPR. NPR, 8 May 2014. Web. 20

Nov. 2015.

Vivarelli, Nick. “Dino Risi.” Variety

11 June 2008: 16. Print.